THE SIXTH DOMAIN OF WARFARE

India considers its defence industry, both public and private, as the “Sixth Domain.”

Synergia Research Team

The leading military on the globe, the U.S., doctrinally accepts five domains in warfighting- land, maritime, air, space, and Cyberspace. The Americans define a military domain of warfare as a medium that “actors need to access, manoeuvre within and through and dominate or control, in order to achieve a military objective.”

Historically, the land, maritime, and, later, the air domains dominated the battlespace. After the Cold War, space was added, followed by Cyberspace. This most recent addition evolved from integrating computers, communications, networks, and control systems in the late twentieth century.

Interestingly, in some papers originating from the U.S. War College, the Bureaucracy has also been debated as a sixth domain- an intellectual space in national security where policy professionals develop, coordinate, and recommend courses of action or statements of guidance for the US government to review, approve, and implement through national-level strategies, policies, and programs to achieve national objectives.

Writing for the Atlantic Council (04 October 2024), Franklin D Kramer highlighted the private sector's role in warfare in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. He points out that private sector companies have been the key to providing effective cybersecurity and maintaining working information technology networks. These operational and coordinated activities by the private sector demonstrate that there is a "sixth domain"—specifically, the "sphere of activities" of the private sector in warfare.

Industry as the Next Domain

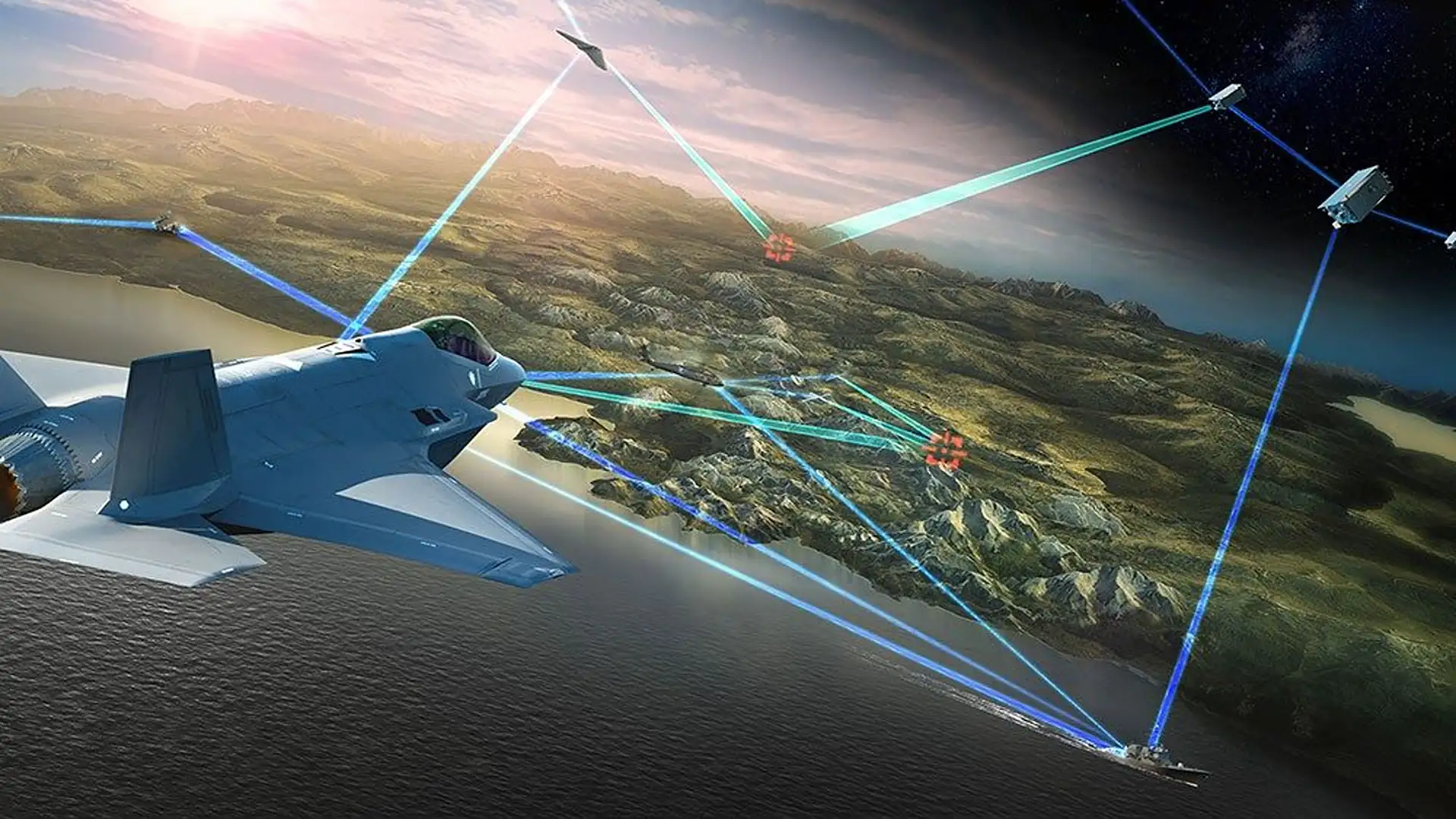

There is a school of thought in India amongst both the military and the civil policymakers that the industry is rapidly becoming the sixth domain of warfare. As technology evolves, doctrines and tactics try to keep up with modern technology, greatly enhancing the military's capabilities.

The Ukraine-Russia war exemplifies this, as the military adapts tactics based on technology encounters. The future of warfare will be driven by information dominance, with cloudification, sensor saturation, AI, and edge computing enabling the shift of technology between civil and military sectors. This will require long-range precision weapons, autonomous and robotics, and a shift in planning processes.

The development of technology often leads to a slow production rate, with an average delivery time of 18 months. This slow rate can encourage the enemy and hinder the deterrence value of own armed forces. Operational evaluation is a weak area in technology development, resulting in technology reaching the front-line soldiers when it is already often obsolete.

Armed forces are shifting from system procurement to R&D and knowledge partnerships to avoid this pitfall, aiming to secure the future.

A New Age Defence Industry

The Indian defence industry has been dogged by a labyrinth procurement process that was time-consuming and designed to delay and procrastinate costly purchases, especially from overseas. However, when India was in its initial development state with little financial flexibility to incur heavy expenditure on defence procurements, such a system played a crucial role in balancing the nation's social development vis a vis it's military needs. As a result, the defence sector has been missing on modernisation.

However, now that India aspires to be a global player, its military power has become a significant element of its national power. Hence, the old systems must be jettisoned to meet the needs of a new emerging India.

This is reflected in the Armed Force's capital budget, which has increased to 1.72 lakh crore, with a modernisation budget of around 1.05 lakh crore. This budget focuses on two important segments: modernisation and committed liability. The budget has a healthy mix of both, with 90% being committed liability and 10% being new schemes. The Armed forces have realised they have no mega capability. The Indian military industry has seen a shift in focus from the public to private sectors. The Indian private defence industry is only 10 years old, with organisations like Tata and L&T being the major players. The government has started focusing on startups and iDEX to create a startup ecosystem, which could contribute 5 per cent of India's GDP by 2035.

The tax regime on defence products, once the highest in the world, has been reduced from200% to 150% in 2019. The French model provides tax breaks over three years, compensating businesses for their efforts.

The government should focus on R&D and create a thousand talent program to attract bright minds to the defence industry. The TORCH program assesses labs for IPR, productivity, and business. The government should provide liberal funding for labs based on performance and funding. Joint papers by researchers, industrypartners and users are crucial for successful funding.

Changing the Goal Posts

The procurement programme of the Indian Armed Forces is guided by its procurement policies.

The Defence Acquisition Planning (DAP) 2020 is a comprehensive guide for armed forces organisations. It covers various categories, such as strategic partnerships and leases, and provides guidelines for registering and obtaining RFI and RFP.

The DAP’s financial bible is essential for understanding the process and navigating precedence cases. The guide emphasises the importance of understanding the processing power and the need for a comparative chart to compare global and industrial standards. Essential and desirable parameters play a crucial role in determining equipment's L1 (Lowest Cost) status, guiding procurement decisions by setting minimum standards and allowing for additional value through enhanced features. The Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) encourages companies to utilise these parameters for structured mapping and comparison. The system engineering concept is also discussed, emphasising the importance of synchronising multiple sessions and understanding the language between users and system designers. The guide emphasises the importance of writing operational concepts as a designer to avoid issues with specifications.This is an important addition as, in the past, there was a big communication gap between the users (the fighting arms) and the designers (public and private) that led to many costly time and price delays in the entire procurement programme.

There is also an emphasis on the importance of investing time and effort in fostering trust with users and ensuring a realistic assessment of competence and compliance. Towards this end, the Army must catch officers young with the ability to understand the procurement process to guide projects to their successful culmination within stipulated timelines. The need to regularly review the project with the user and team members and break down major challenges into smaller ones is vital. It also emphasises the importance of forming a collegiate group to ensure compatibility and survival. As of date, 80 per cent of startups in the US military domain fail, but if all members form a like-minded group, they will at least survive. Retired technically adept military officers must be employed to assist in testing and field trials so that their experience can be gainfully harnessed.

The armed forces require a contract with a minimum of 100 crore for a long-term support system, with the government DPIIT requiring a minimum of 100 crore for startups. The DAP allows companies to bid without a stamp of defence, but entry barriers exist. The defence sector is focusing on processing power, communication, and electronic warfare, with a focus on GPU and supercomputers.

Defence production must adhere to global certification for all new products, whether drones, electronic warfare equipment, or missiles. It also emphasises the need for mutual recognition of certification processes within G7 countries and the need for specialised teams to ensure compliance. It is important to have open architecture, modularity, safety, cyber security, physical security, EMI, and EMC.

The Way Ahead

It is important to have a good supply chain management and risk mitigation strategy to ensure success. To ensure high-quality logistics, it is essential to have a secure and diverse supply chain with reliable back-end partners across the length of the supply chain. Partnerships must be forged with indigenous and certified sources for quality assurance and certification to address pain points in the industry, such as think tanks and academia. We must also map the existing ecosystem, such as IIT or NIT, to develop and nurture talent.

While Atmanirbhar is the ultimate aim, it cannot be achieved in isolation. The importance of international cooperation in the field of cybersecurity and technology cannot be overlooked, including the need to avoid becoming a technology colony and focus on export opportunities. To encourage exports, the potential for capturing specific markets for export should be part and parcel of the DPP, especially in areas like space where Indian industry has some lead. India has carved for itself a strong presence in the Quad and this should be leveraged to encourage technology partnership between members of the Quad, especially in the defence sector. The Wilmington Declaration has an important paragraph on cooperation on semiconductors, R&Dcollaborations in Critical and Emerging Technologies and enhanced partnerships in cyber and space.

However, the greatest change must come from within the Defence Forces themselves as they reconfigure themselves from mere procurement to becoming knowledge partners. They must take the lead in emphasising competition and innovation as they partner with R&D and academia to share their pain points and create new business opportunities.