From taxes to embargos – what does it take to achieve goals on climate policies?

The year has seen some significant initiatives being mooted on the climate change front by forcing action through drastic policy interventions. On May 18, the International Energy Agency (IEA) called for a ban on exploring and developing new oil and gas projects as part of their ‘net- zero by 2050’ plan to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Earlier this month, in a virtual Petersburg Climate Dialogue, German Chancellor Angela Merkel proposed a ‘CO2 price worldwide’ to keep global emissions in check worldwide. She called for further discussions on interventions to assist developing countries struggling with the financial burden of the climate crisis.

HIKING THE COST OF POLLUTING

Considered an effective tool ‘for meeting domestic emission mitigation commitments’, tax on carbon consumed is intended to address the ‘silent killer.’ It is hoped that it will make visible the hidden social costs of carbon emissions, which are otherwise felt only in indirect ways – like climate change and on one’s health. Countries that have already implemented a carbon tax policy have priced it too low to make a dent in global emissions. Without interventions to mitigate the accumulation of carbon dioxide, future generations will experience an increased risk of respiratory conditions, climate events, and destruction of the natural world.

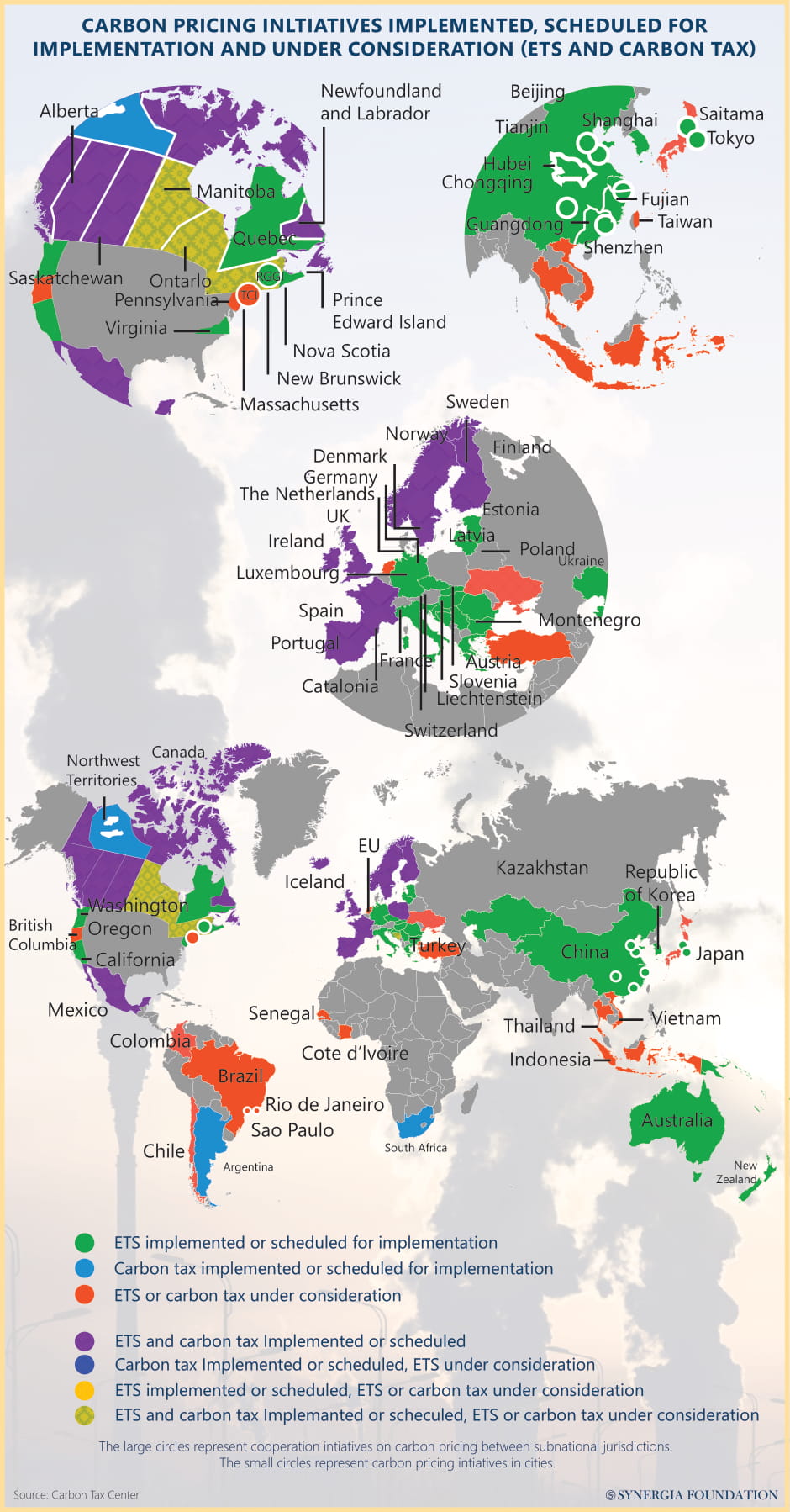

The primary motivation for supporting carbon taxation has been its potential to meet domestic emission mitigation commitments and produce benefits such as reducing air pollution, which is a prevalent health crisis in many countries. Many countries like China, the U.S., UK, and New Zealand, among others, have systems in place that enforce a carbon limit by pricing carbon emissions in the form of tax or an emissions trading system (ETS).

Despite the noble intentions of these states, enough loopholes remain to bypass the ETS. Since carbon tax is not presently applied uniformly across countries, companies locate their manufacturing in low carbon tax companies leading to a ‘carbon leakage.’ In the case of the EU ETS, critics point at its ridiculously low prices, making it hardly a deterrent. Sadly, little research has been gone into assessing the actual volume and prevalence of carbon leakages. One study in the EU concluded that a border tax on carbon emissions could lower leakage rates and reduce overall emissions by 5 per cent. But due to the global economic inequity, the impact of implementing an international carbon tax appears detrimental to poorer countries at first glance.

The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research identified that 400 million people worldwide would live in extreme poverty by 2030 if a global carbon tax is implemented (without considering the socio- economic effects of the pandemic). It is not surprising that, therefore, carbon tax interventions have repeatedly failed to gain political will. It is not the best first option in climate change intervention as it does not consider externalities that are potentially more important than the direct damage of climate change itself.

BIG OIL IN SOUP

Oil companies have been criticised for their disinterest in climate plans despite being the biggest contributors – for ‘not including all their products, treading too slowly, and being overly reliant on carbon offsets’.

The IEA’s recent announcement is significant in that it has inadvertently caused a bandwagon effect for other major players in the industry to follow suit. A Dutch court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to cut its carbon dioxide emissions 45 per cent below its 2019 levels by 2030. An activist hedge fund that favours renewable energy won two seats on oil giant Exxon Mobil Corp’s board. Considering that Exxon has previously mainly selected its directors for their 12-member board, the move is remarkable. It may spur more activist investors to push for reform and influence overall investor decisions.

A small activist hedge fund (Engine No 1) promoted these new “green” members by garnering the support of some of Exxon’s most prominent investors. American investors are now asking energy companies to shift their business models as climate change intensifies. Shanghai Chevron investor confab voted an emission cut plan for the consumption of its products, placing upon itself the onus for the pollution its customers create when burning its oil and gas. Net-zero targets between 2050 and 2060 already cover 70 per cent of the world. A key criticism that these climate policies receive from OPEC and other climate activists is that the decision opens risk to price volatility while the goal of achieving net-zero emissions seems over-ambitious.

OPEC further argues that without an inclusive policy that accommodates countries within different levels of economic development, it will be difficult to transition to renewable energy.

Assessment

- International players must work committedly towards sustainable carbon policies. Policymakers have to ideate pragmatic and equitable policies that ensure mitigation, taking cognisance of the nuances in regional frameworks that inadvertently influence consumer behaviour.

- While carbon tax alone will not solve rising temperatures and climate change, it is a significant first step towards Net-Zero. A progressive introduction of carbon taxation would allow businesses and individuals to adjust. It would be in the interest of countries like India and China when the benefits from reduced air pollution mortality are considered – a $35 a ton carbon tax in 2030 would save an estimated 300,000 premature deaths a year in China and approximately 170,000 in India, as per research.

- Developing countries need to be encouraged to make the green transition. A floor price that differentiates according to economic development accompanied by an international finance redistribution scheme for the climate sector would benefit the developing countries.